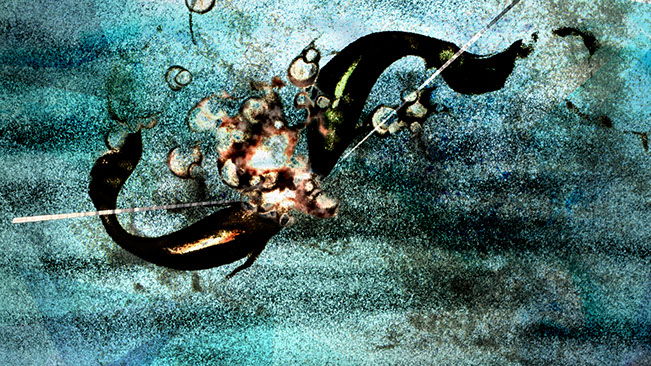

Rock glacier-inspired animation by Corrie Francis Parks

A talk with Corrie Francis Parks in Vienna on March 23, 2023

Stefan: Dear Corrie you are an animation artist and you’re here as an artist in Residence in Vienna. Please tell us about yourself and your work.

Corrie: Yes, I consider myself first and foremost an animator! I am based in Baltimore, on the east coast of the United States. I guess I started animation in a more traditional sense but my career has taken an experimental turn. I primarily work with sand, but I also use a lot of digital techniques in order to create complexity and discover new ways of animating with that material.

Stefan: What does experimental practice mean to you?

Corrie: It’s good that you asked what it is specific to me because I think everyone might have a different answer to that question! When I work in my studio, I’m working a little bit like a scientist. I’m trying to find new ways to move the sand, new ways to see the sand, to make the sand come alive. When I first started doing sand animation I did it in a more traditional way where you put sand on a glass lightbox and you draw with the sand. My debut film, “A Tangled Tail” (https://vimeo.com/78802560) used that method, but I also wanted it to stand out from traditional black and white sand animation. Since I was shooting digitally, I invented some new ways of compositing layers and adding color using After Effects to create a unique look that really hadn’t been done in sand animation before. I want my films to be something that has never been seen before so I think an experimental practice is trying to figure out how you create something new. Both something that’s new in the production methods but also new in how it looks or the way it communicates.

Stefan: Could you give an example?

Corrie: I can talk about the project that I’m working on while I’m here in residence. It is about rock glaciers. These are geological forms and there are thousands of them in the Alps, but you have to know how to look for them. They are piles of rock with ice inside. The rock might be three or more meters deep and it insulates the ice, so the ice doesn’t melt as fast as a glacier that’s out in the open. So they’re very good ways of storing water for the environment, even in the face of climate change. They also look very cool! From a distance they look like piles of sand and they move because the ice freezes and the ice thaws and that makes the rocks creep forward in these interesting folds. So that was the point of inspiration for this project that I wanted to somehow create that type of movement but on a small tiny scale using sand. In the studio I’ve been experimenting with the process of freezing sand and water and then letting it melt and then freezing it and melting it again and layering it the way that layers happen in geology and then seeing what the results are. And the results are quite interesting visually, but very hard to control. It’s a type of movement that you can’t make with human hands, you can only make if you collaborate with the physical qualities of nature. I have been experimenting and testing out different approaches to this ideas for three years in my studio practice and so some of the results will be in the installation.

Stefan: Do you use the results of your experiments for storytelling, do you think of your audience, or is it just an experiment for yourself?

Corrie: It’s been changing a little bit. I think earlier in my career I was more interested in telling stories and now I’m more interested in people having an experience or maybe presenting an idea that someone might not have thought about before and then they have something to think about after seeing this interesting animation or installation. So I am thinking about my audience, I am thinking about how they can connect to the idea and the point of inspiration, and how they might think of the work. But I’m not necessarily trying to tell a linear story.

Stefan: You talked about the geological aspect of sand, you also mentioned the term Deep Time.

Corrie: Deep Time is geological time. It is thinking about time on the scale of the earth rather than a human scale. Because I work with sand I’m always thinking about scale. The earth has been around for 4.6 billion years, which is sort of a meaningless number to us humans. A human lifespan might be 80 years and maybe our human memory goes a generation or two behind to our grandparents or a generation or two ahead to our grandchildren, but that’s about all we can comprehend. So when we are confronted with the evolution of the earth over these billions of years, our experience is an incomprehensibly small piece of that. We say climate change is an earth sized problem, but really it is a human sized problem because the earth has been through much more volatile changes and it is just fine with that. We (humanity) need to solve this problem for ourselves so we can continue living on the earth. We are very attached to the earth in its current configuration, because it is all our human memory can conceive, but perhaps adopting a Deep Time perspective might allow us to think of some solutions that we can reasonably implement given the political and social context of our society.

Stefan: Is this a conclusion you drew from your experimental filmmaking or is it an idea that your filmmaking is based on?

Corrie: It’s an evolving thought in my head, and certainly influenced by other artists who address the subject of time, and also the research I’ve done in geology and the history of science. It’s also tied to the fact that I spend a lot of time in the mountains. I really love being in the mountains, hiking and skiing and being in nature. I’ve been working with sand for 20 years and I have sand from many different places in the world. Sand is like human beings. When you have one little grain of sand it has its own story and its own history and it’s beautiful all on its own but then you put it in a big desert and it gets lost. Those metaphors have all filtered into my films and installations. I’m still grappling with it. I haven’t come to any conclusions and I think it will probably be a theme for a while because I’ll continue working with sand.

Stefan: You obviously like the material itself, but in filmmaking the original material gets transferred into media pictures. Now you’ll be doing an installation at the ASIFAKEIL here at the MuseumsQuartier where you would have the opportunity to work with the material itself. What are you planning for this exhibition? What do you think about the increasing use of animation in the art world and how do you like ASIFA Austria’s quite peculiar showroom?

Corrie: Those are all things that I have been thinking about in the last month and thankfully I have a little more time to figure it all out! When I approach a space or an installation project I work very intuitively. I have a thematic starting point, in this case, the rock glaciers, and then I have to put things places and move things around and try out different materials. It is important to me that animation finds a way into the installation, but I also am averse to just having the box of a monitor or a projection, I want to somehow relate more to the shape of a space. That’s why the ASIFAKEIL is a really intriguing place to work because it’s such a strange space with so many different angles and narrow points that you’re really forced to think outside a rectangle. I think there will probably be some real sand in the space. In September I collect some samples of sand from different rock glaciers in the Alps, but I honestly don’t have enough of it to fill anything big, so whatever is in the installation will be something that’s very small. Maybe there is a conversation to be made about the small reality of grains of sand and what they look like when they’re moving on a screen.

Stefan: It’s also about the appreciation of the material. Sand stands also for something limitless, available in huge amounts like in the desert. But in a small scale you can give it a special value. There’s a philosophical or almost religious aspect connected. You could put a bowl of sand on an altar and worship it.

Corrie: Actually I’m planning an exhibition in October and there will be a bowl of sand on a pedestal! What I think people find fascinating is when you can look closely at something you never looked at closely before. Like you said, you’ve gone to the beach you’ve gone to the desert but you never paid attention to the actual sand other than to walk on it or to build a sandcastle, but maybe when you look very closely and see what each little grain looks like then it it makes you think about something differently than you normally would.

Stefan: Switching between the single grain and the limitless amount of sand in a desert for example is something interesting…

Corrie: That is something that I’m still exploring, how close and how much sand is effective for the particular idea that the animation is about. In this particular piece about the rock glaciers there’s more like a handful of sand that’s moving as one creature in some way. Whereas in some of my previous work we really looking at just one grain of sand two grains of sand and how they relate to each other. So those are still things that I find really interesting to play with and to explore- How close can you get or how individual and what does the individuality mean?

Stefan: Sand stands for the end of an evolution like an eroded mountain, but then again it’s the start of something new being, for example, part of construction material. The lifeless material becomes something new showing perfectly the animistic aspect of animation.

Corrie: I think the the transformational qualities of sand that you’re referring to are part of its unique quality. It can really change form, it can morph and interlock in certain ways to become something new. That’s what makes it an interesting material to animate, you can draw with it, you can make shadows with it, you can look at it as one little piece or in a big pile. It is three- dimensional and it’s two-dimensional at the same time. I think that’s why I keep working with it as an artist.

Stefan: Thank you very much, Corrie.

Corrie: You’re welcome.

freeze/thaw: Rock glacier-inspired animation by Corrie Francis Parks: https://vimeo.com/811814563

www.corrieparks.com

www.asifa.at